A Brief History of Academic Freedom in The Global North: A Literature review.

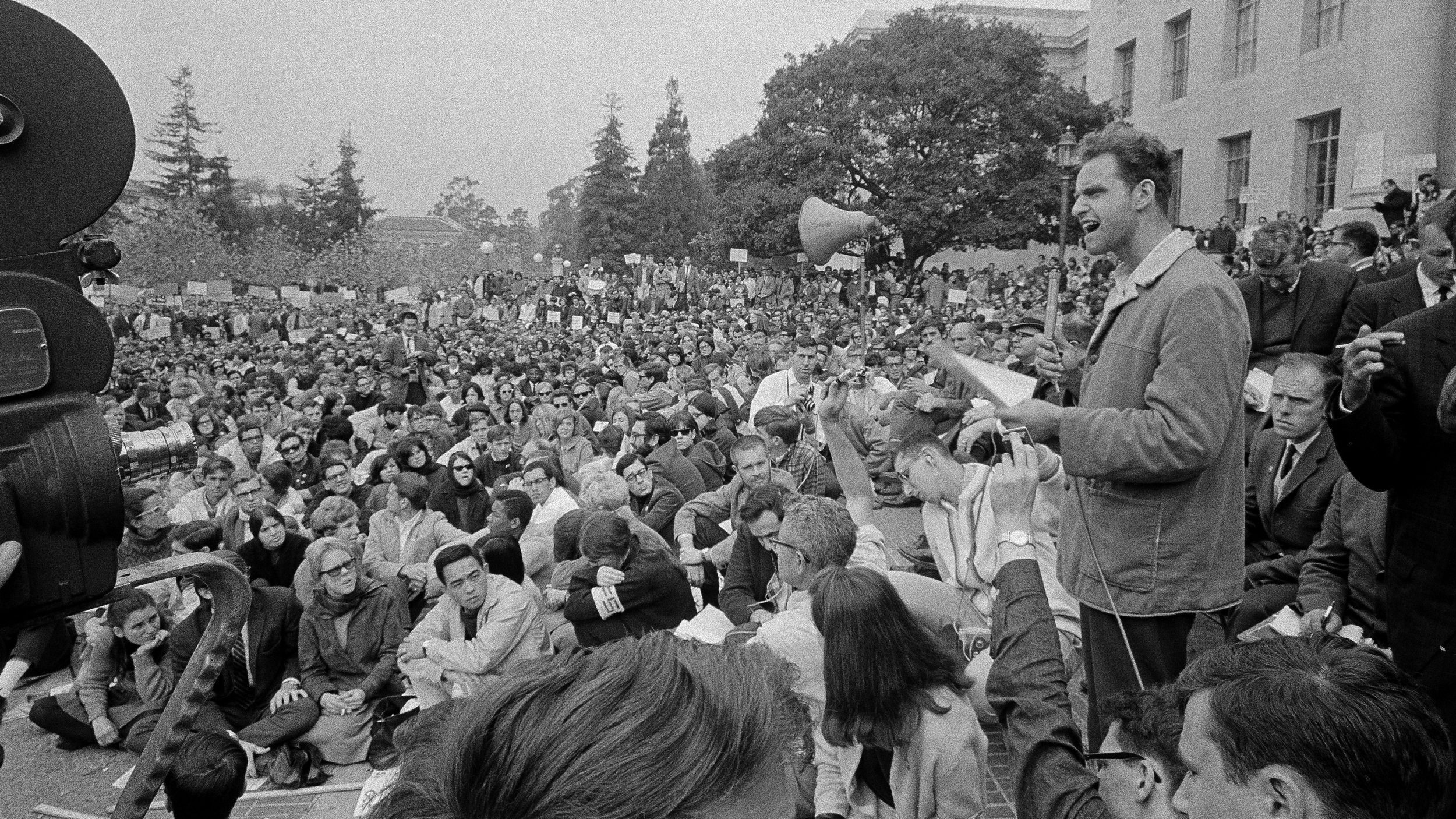

Mario Savio speaks out against academic censorship during a student sit-in during the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley, c. 1965.

Debate concerning academic freedom is one that has gained impetus and recognition amongst scholars throughout the last decade. This review will outline the broader philosophical conversation in scholarly literature on the issue, then proceed to analyse perspectives on the politicisation of academic expression pertaining to structures of censorship. Finally, I examine transitions within dominant ideologies on the matter in relation to the Berkeley Free Speech Movement of 1964, as what scholars consider a movement marking the origins of the debate within Western academia.

Scholars unanimously agree on the role of the university as an arena for the unfettered exchange of ideas in which a truth-seeking mission must be prioritised. It is in the act of defining free speech and academic freedom that divisiveness occurs. Multiple scholars reference First Amendment rights as the rationale employed by Liberals in their advocacy for academic freedom (Wright, 2018), Leftist scholars arguing against it. Fish (1994 as cited in Wright, 2018), an advocate for the prohibition of hate speech, argues that “First Amendment principles are an empty abstraction” (p. 393) and that defining the legitimacy of speech is within itself a political act. Similarly, Scott (2016) echoes this sentiment, signifying that there are no “absolutes” (p. 1) in free speech.

The majority of literature on the subject compares stances on the issue from liberal-conservative, and progressive perspectives (Wright, 2018). Scott (2016) and Waiton (2021) arguing that historical developments on the issue span from the stronghold of Conservative Liberalism over matters of academic censorship, as in the Free Speech Movement, to a now perceived infringement on Liberalist values by those deemed as progressive. A popular argument in advocacy for the regulation of speech put forward by scholars like Fish, Kessler, and Wing-Sue (as cited in Wright, 2018) is that the prohibition of microaggressions and hate speech led to more inclusive environments which effectively promote the status and perspectives of marginalised students. It is important to note the imbalance in the profusion of sources debating the issue in relation to marginalised groups, and lack of direct inclusion of marginalised perspectives within the sources themselves.

Wright discusses the implications for the left’s ideal of censorship and academic freedom, providing a convincing proposition for future censorship policy to adopt a ‘bottom-up’ decentralised approach. This, Wright argues, will allow for greater ethical practice in academic gatekeeping and campus speech governance namely through the production of a “polycentric order” (p. 396). Similarly, Waiton (2021) concludes that the power to influence censorship policies now stems from within universities, suggesting a shift in pressure exerted over academic freedom, from external institutions (Cohen & Zelnik, 2002) to internal actors. Both Waiton and Wright argue that the regulation of microaggressions and self-censorship can be classified as responses to new structures of censorship in higher education.

Ultimately, developing narratives reflect the sentiment held by Berkeley campus chancellor Clark Kerr in 1964, that universities are inherently transformed by the societies of which they form part (Hinman-Smith, 1993). Censorship trends favouring Leftist concerns can thus be seen as a reflection of both the increased heterogeneity (Scott, 2016) of both 21st century university cohorts alongside broader ‘consciousness’ movements within society. I believe that future policy development on the issue would benefit from a consideration of arguments from both ends of the political spectrum to achieve a nuanced and ethical result.

References

Chamlee-Wright E. (2018). Governing Campus Speech: a Bottom-Up Approach. Society, 55(5), 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-018-0279-1

Hinman-Smith, D. (1993). "Does the word freedom have a meaning?" The Mississippi Freedom Schools, the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, and the search for freedom through education. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Savio, M. (2022). Thirty Years Later: Reflections on the FSM. In Cohen, R. & Zelnik, R. (Eds.), The Free Speech Movement : Reflections on Berkeley in The 1960s (pp. 57-72). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520928619

Scott, P. (2016). Free speech and political correctness. European Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), pp. 417–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2016.1227666

Waiton S. (2021) Examining the Idea of the ‘Vulnerable Student’ to Assess the Implications for Academic Freedom. Societies, 11(3), 88-88. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030088